The Keep film by Michael Mann

Written by Kit Rae (and friends) in 2005. Last update June 2025.

PAGE 2 - BACK TO PAGE 1

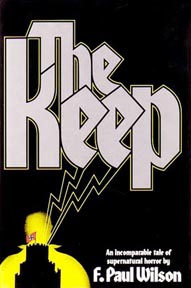

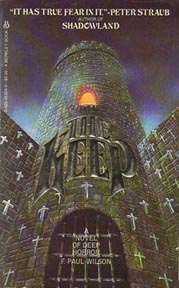

The Keep film title (left) and the novel by F. Paul Wilson - 1981 hard cover and 1982 soft cover

THE MAKING OF THE KEEP MOVIE ADAPTATION - The Keep was a gothic horror novel set in the Carpathian Alps of Romania during World War II about a German Army outpost stationed in a strange medieval fortress. They accidentally awaken an ancient evil named Molasar, who masquerades as a vampire in an attempt escape from the keep that imprisons him. The book, by author F. Paul Wilson, was published in 1981 and made the New York Time best seller list. Being an avid horror novel reader, Wilson's book was on my reading list in 1982. While it had some interesting ideas, and I know several people who loved the book, I found it to be a bit bland for my tastes. Not a bad book, just a bit average, but I enjoyed elements of it and was excited to hear not long after reading it that a film version was in the works. I was even more excited when I heard Michael Mann was to be the director. I was a huge fan of his 1981 film Thief, and its score composed by Tangerine Dream. The Keep, released in December 1983 by Paramount Pictures, starred Scott Glenn, Jürgen Prochnow, Ian McKellen, Alberta Watson, and Gabriel Byrne. It was very different from the book, with a very odd story structure, but I found it to be much more interesting and engaging in places than the book. At the time many fans of the book and the film critics felt the exact opposite. However, most people agreed that The Keep was beautifully filmed, with incredible production design and music score. Although it was somewhat lacking in the second act, I thoroughly enjoyed it and it was one of those films that I could not get out of my mind for a long time afterward.

The Keep American insert movie poster

After reading all the interviews and articles about the film that I could find in the following year, it was clear that Michael Mann never intended to make a straight adaptation of the book, but had other things in mind for his film version. It also became clear that the film released in theaters was itself far from the film Mann intended to make. Production delays, budget problems, and studio interference made The Keep into a film Mann considers a "butchered" version of his original idea.

Michael Mann on the set of The Keep in 1982 with actor Scott Glenn (right)

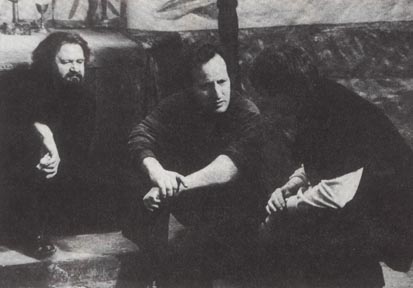

Michael Mann on the set of The Keep the keep at Shepperton Studios in 1982 with actors William Morgan Sheppard and Jürgen Prochnow

Going back to the source material, apparently Mann did not care much for the somewhat generic elements of Wilson's horror book, especially the vampire references. He still found some fantastic elements to work with and used the basic plot and setting as loose basis to write his film version, which explored different themes and ideas through the characters. His inspiration came more from the Gabriel Garcia Marquez book, One Hundred Years of Solitude, and Bruno Bettelheim's book The Uses of Enchantment. He was interested in building the self contained reality of the world created in the film to present a universal morality tale that reflected our time, an 'adult fairy tale' as he called it. I think the truncated film released only partially succeeded in that area, but the film worked on other levels.

"Initially I didn't care much for the book, but then I realized it contained something fantastic. I rewrote, and then took the screenplay in a direction the book doesn't go, with the idea of doing a fable. It's a fastinating form - you don't have to deal with the origins of things in terms of natural phenomena or natural causes...you don't have to explain how or why; it's all accepted. You can just channel the characters into metaphor." - Director Michael Mann from Sight and Sound, September 1982

"Let's face it, the book was very messy. I saw more potential than the existing application. The novel was the usual sort of solid gothic horror, and I wanted to do something more expressionistic and basically make the whole thing as a dream...I mean the vampires were out immediately. It's nonsense and it has all been seen before and I'm just not interested in doing something that has been seen before or a variation on that theme. This is a very ambitious film to make as I want to make you feel in ways you only feel once every two months or so when you have had an erotic dream or terrifying fantasy. The mechanism of events, as I see the story now, are repressed urges and desires in the unconscious mind that has to motivate the characters themselves in the story events themselves. And that is quite a departure from the book...this setting, that Paul Wilson chose for his story, works very well in the context of a fairy story for adults. I don't know what Wilson thinks about my changes to his story. We talked briefly and he did send a telex with some suggestions but when we are making a movie, we are doing just that. The book is the raw material to change into what the movie has to be" - Director Michael Mann in 1983, from Starburst magazine

In 1983 a television interview with Michael Mann was broadcast on The Electric Theatre Show (viedo linked above). Mann talked about the power of dreams, and moving The Keep story out of the horror genre of the novel and into a dream reality. He felt it was not necessary to try and explain non-natural events or causes because they are states of mind in an expressionistic dream reality, which is what he was attmpting to do with in his film version.

Director Michael Mann on set and the film synopsis from The Keep Handbook of Production Information (click to enlarge)

The first draft of Michael Manns's screenplay (click to read)

Michael Mann on the set of The Keep in 1982 with actors Jürgen Prochnow and Scott Glenn (left), and Robert Prosky (right). Prochnow is holding a historically accurate MP38 submachine gun, one of many period correct props.

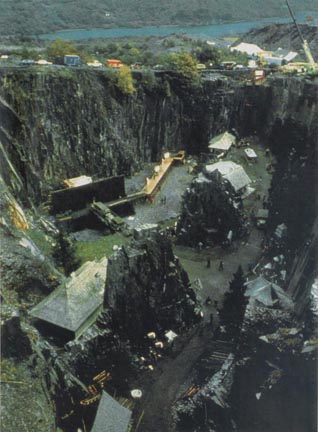

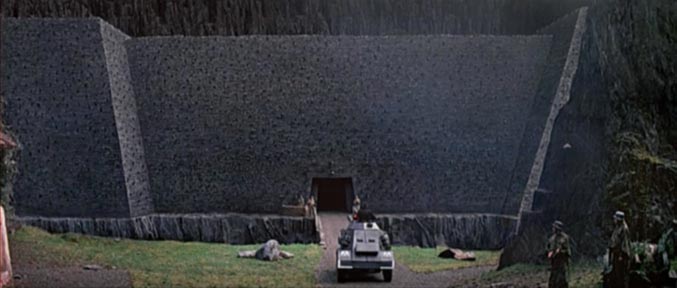

(left) The village set, built in the disused Glyn Rhonwy slate quarry located in Llanberis, North Whales. Dolbadarn Castle is also located in the Llanberis Pass, with a stacked slate construction similar to that used for the keep movie set. (right) The interior courtyard set for The Keep under construction in 1982 at Shepperton Studio Centre, in the United Kingdom. Interior courtyard wall sections were molded in plaster, made from castings taken at the quarry.

The village set and front wall of the keep under construction in the bottom of the Glyn Rhonwy slate quarry in Llanberis, North Whales

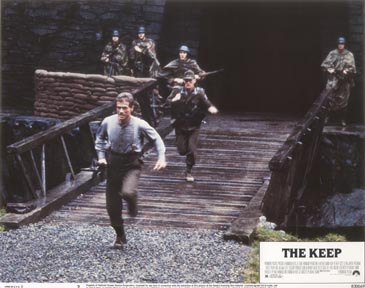

The front wall of the keep with moat and bridge as seen in the film

The village set built in the bottom of the Glyn Rhonwy slate quarry as seen in the film. This scene illustrates one of the few historical inaccuracies in the film's costuming: the SS Allgemeine division who wore the black uniforms, insignia, and arm bands shown in the film were never stationed outside of Germany.

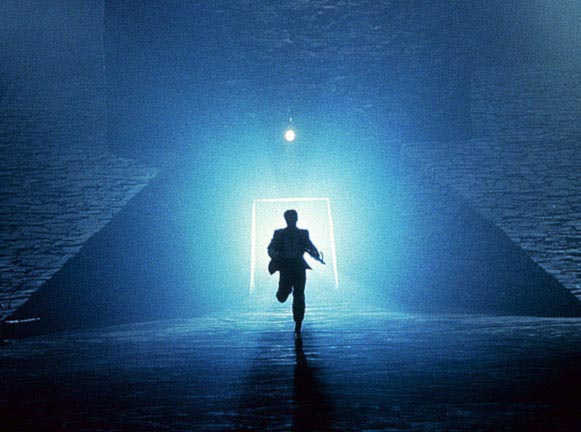

Some scenes inside the keep, and the the sub cellar beneath the keep, were filmed in the Llechwedd Slate Caverns in the Snowdonia National Park, near the slate quarry used for the village set.

Press release photos of actor Jürgen Prochnow as Captain Klaus Woermann and William Morgan Sheppard as Alexandru, the caretaker, on the set of The Keep at Shepperton Studios

Press release photos of the interior set of the keep at Shepperton Studios.

The film was an ambitious project with a relatively large 6 million dollar budget, considering the genre. John Box (Lawrence of Arabia, Sorcerer, Rollerball) was hired as the production designer and Alex Thomson (Fahrenheit 451, Superman, Excalibur, Legend, Alien 3) was hired as the cinematographer. Wally Veevers (2001: A Space Odyssey, Excalibur, Superman, Saturn 3), who would pass away during post production, was hired as the visual effects supervisior. Filmed in the United Kingdom, the massive sets of the interior of the keep were constructed at Shepperton Studios under the direction of Box. A difficult project was undertaken to clear out the bottom of the disused Glyn Rhonwy slate quarry located in Llanberis, North Whales, where the entire Romanian village set and the front facade of the keep were built. Scenes deep inside The Keep and the cavern below it were filmed in the Llechwedd Slate Caverns in the Snowdonia National Park, located a short distance from the slate quarry. I found the look of the quarry set and the interior of the keep in the film very strange and unique. I have never seen anything quite like it before or since the films release.

Every effort was made to use historically accurate military costumes, weapons, gear, and vehicles for the Heer and SS soldiers, something rarely done in films depicting the German army. Mann started filming on September 20, 1982 without a finished screenplay and was constantly rewriting dialogue during shooting. It was rumored that nearly the entire budget allocated to make the film had already been spent by the time filming began. By all accounts, Mann was a very demanding director who faught to make the best film possible, but many of the crew felt like they were in the dark about what they were doing. It was a difficult 13 week shoot, with very long hours, and only got harder and messier as time went on. After principal photography had finished, there were additional reshoots that extended the filming for another grueling 22 weeks.

German electronic group Tangerine Dream, who had scored Mann's previous film Thief, were contracted to create the musical score for the film. According to the production handbook the production schedule required them to start composing the music in September 1982, before filming had actually begun, only using an incomplete script and Mann's story boards for inspiration. They recorded the final music to use in mixing the actual score In February 1983, using a rough cut of the film, with no completed ending.

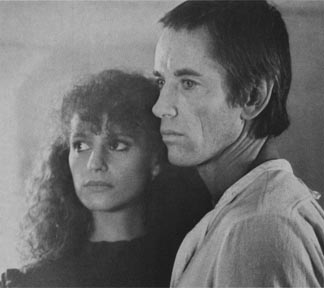

The Keep press release photo of Scott Glenn and Alberta Watson

Special mechanical effects artist Nick Allder and special makeup effects artist Nick Maley were responsible for the various forms of Molasar (the film's golem-like villain) seen in the film. Allder has stated that he had a lot of problems creating Molasar costume because Mann did not know exactly what he wanted, resulting in an enormous amount of time spent building numerous costumes that were never used. At least 15 different versions of Molasar were built, but only three appear in the film. French artist Enki Bilal was brought in by Mann to redesign the final stage of Molasar towards the end of production, resulting in a costume that was more to Mann's liking. According to Allder, it was not as detailed as the original costume. Bilal thought it was a bit too muscular and shiny, but was pleased with it. Actor Scott Glenn thought it looked like the Michelin Man! (a character made of tires used for Michelin's advertising)

Production woes escalated when the film was delayed for six months due to the unexpected death of visual effects supervisor Wally Veevers shortly into post production, causing the ending to be re-worked. The film was already over budget and this delay added even more to the cost, which had ballooned to 11 million by some accounts. After all the production troubles, the film's June 3rd 1983 release date was bumped back to December 16th. It only got a limited release and very little advertising. It performed poorly at the box office, was panned by most critics, and was a financial flop. However, enough people liked the film and 'got it' for it to gain a cult following in subsequent years. Tangerine Dream's unique music score was one of the driving factors in the films continued popularity.

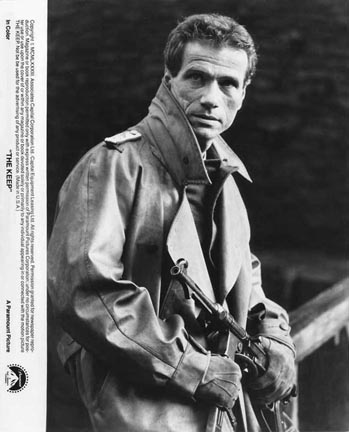

Press release photos of actor Jürgen Prochnow as Captain Klaus Woermann

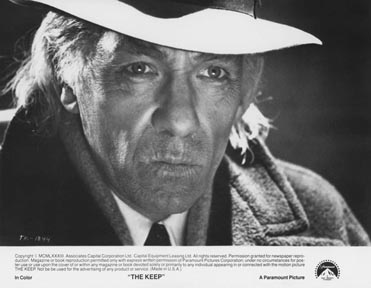

Movie still (left) of Gabriel Byrne as Major Kaempffer, and press release photo of Ian McKellen as Dr. Theodore Cuza (right) with old age makeup

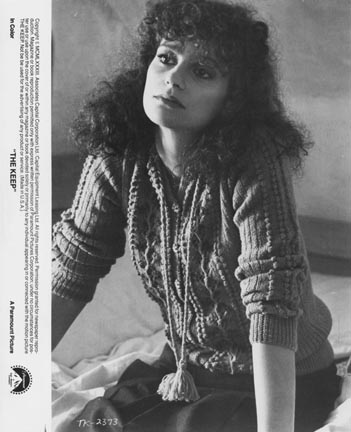

Press release photos of actor Gabriel Byrne, Alberta Watson as Eva Cuza, Ian McKellen, and Jürgen Prochnow

Press release photo of Gabriel Byrne, Alberta Watson, and Ian McKellen.

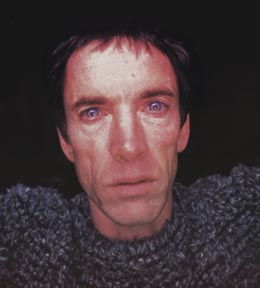

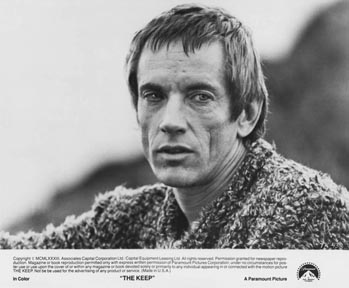

Press release photos of actors Alberta Watson and Scott Glenn, as Glaeken Trismegestus

A TROUBLED POST PRODUCTION - Mann had several ideas for the final battle between Galeken and Molasar and ending of the film. Several versions were filmed. Visual effects supervisor Wally Veevers was in charge of creating the fantastic, dreamlike effects footage for the battle. Hours and hours of stunt footage was shot with actors Scott Glenn and Michael Carter, as well as various effects elements that were to be composited together to complete the shots. Unfortunately, much of the footage became unusable after Veevers untimely death just two weeks into post production. It was a devestating blow that the production never recovered from. Veevers reportedly never wrote anything down and had no story boards. It was all in his head. No one knew or could figure out exactly how he intended to combine and use of the strange the unfinished optical effects footage he had shot. According to actor Scott Glenn, approximately two thirds of the footage remained unfinished and unusable.

"Michael Mann was hesitating between two different endings. He was not sure whether the finale should take place in the bowels of the keep, Molasar's lair, or on top of the keep. Ultimately, we kept the subterranean ending, but a shortened version of it, because of all the technical problems. The second ending was more like an old Douglas Fairbanks movie. I was fighting with Molasar at the top of the keep. A huge ray of light then blasted up through the center of the keep and took both of us. As the floor is opening up we fall, and keep falling. We were then leaving space-time, a bit like in 2001: A Space Odyssey. I was hanging from wires. But after Wally Veever's death, Paramount would not agree to give us more money, and would not let us finish what we had begun to shoot. At least three important scenes were abandoned because of that..." - Scott Glenn, from the April 1984 issue of Starfix magazine (translated from French)

Mann had to re-think the ending, as well as figure out how to complete all the optical effects shots, so the release date was pushed back six months. Another problem was that he was never happy with the Molasar costumes that were filmed. Veevers was supposed to work with him on re-shoots of those scenes using the new costume Enki Bilal had designed. The crew and original cinematographer, Alex Thompson, had long since left the production, so a new director of photography was brought in and Roy Field (Superman III, Krull) took over the post production optical effects work. All of the Molasar scenes were re-shot with the new costume, as well as the new finale between Molasar and Glaeken, but results did not quite match up to the rest of the film shot under Thompson's lense.

These re-shoots were expensive, adding millions of dollars more to an already over budget film. The filming was now running 22 weeks past the oriiginal 13, and Mann showed no signs of stopping. He kept having sets rebuilt over and over and re-shooting scenes. The producers finally had enough. Paramount called a halt to production and refused to pay for additional filming needed for three additional scenes Mann said he required for the climactic battle. He was forced into an unsatisfactory compromise, assembling a much shorter and more simplified finale for the film from the incomplete footage that had been shot.

A DISASTER OR A NEAR MASTERPIECE? - The look of the movie would probably not stand out to modern day audiences used to the digital effects realm, but for the time it was made, the film was visually stunning and darkly majestic. Except for a few animation effects created under Roy Field's direction (the replacement visual effects director) that were sub-par for the period, and the somewhat cheap, rubbery appearance of the the Molasar costume in the last act of the film, the special visual effects and creature makeup effects were very effective. The grim sets by production designer John Box and cinematography by the legendary Alex Thompson were simply beautiful and mesmerizing to look at.

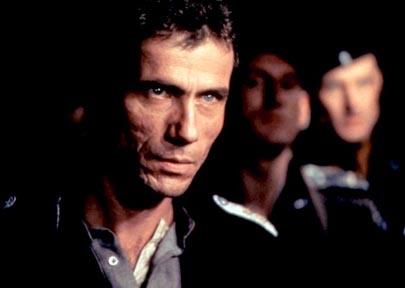

The actors, for the most part, were very good, especially the stand out performances by Jürgen Prochnow and Gabriel Burne. Some of the other performances were intentionally strange, like Scott Glenn's odd acting and speaking style in the film. The Keep aslo features one of the worst performances by one of my favorite actors, Ian McKellen. He has made it clear in interviews that he did not have a good experience on the film, primarily due to the hours of old age makeup application that he had do endure daily, but also due to the character's accent. Prior to filming, McKellen travelled to Romania to learn to speak with a Romanian accent. Then on his first day of shooting Michael Mann asked him to speak with a Chicago accent, which he was not able to do successfully. McKellen said things just "got worse from there". Mann also had others in the cast speak with an odd mix of intentionally out-of-place accents. Some German characters, as well as the villagers, speak with American or Chicago accents, while others speak with German accents.

The film did successfully hold the dark mood of its story from beginning to end, partly due to the unique musical score. However, great music and visuals are only half of the battle in making a film of this type work. Characters and story are the other half, and many viewers felt The Keep suffered in that area. Or was the minimalist approach to character and story intentional?

Actor Jürgen Prochnow on the set in front of the entrance to the keep, filmed in a disused slate quarry in Llanberis, North Whales, and inside the keep set at Shepperton Studios (lobby cards and press release photos)

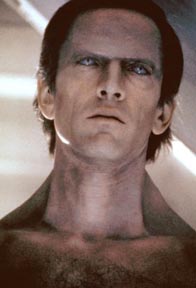

The film is a dreamlike mix of several genres - part horrific fantasy, part sci-fi, part WWII drama, and part social commentary on fascism and the real evils that mankind does to itself. It comes across as a rather odd mix of those elements, and the sometimes odd dialogue and acting styles, also add to the unsettling, dream-like strangeness of the film. Adding more to that strangeness, there were subtle clues that Mann intended the hero and villain to seem otherworldly, or from another time, rather than the more gothic hero and villain archetypes the setting would imply. This is evidenced by the green blood, futuristic technology in the form of Glaeken's staff, which exhibits machine-like sounds and movement when activated. Glaeken's eyes transform into a mechanical grid pattern when he confronts Molasar and his physical body transforms, making his appearance non-human. His body also heals itself in the climax of the film and he implies he is immortal to Eva in one line of dialogue. The press kit for the film confirms that Glaeken was immortal and longed to be a mortal man (something retained from the novel), indicating that there may have been more cut footage or dialogue that expanded upon this, other than the one line that remains in the finished film.

Blue tinted movie stills of Jürgen Prochnow, Ian McKellen, Alberta Watson, and Robert Prosky on the keep set at Shepperton Studio Centre

Movie still of Alberta Watson at the Glyn Rhonwy slate quarry set in Whales

Actor Scott Glenn as Glaeken Trismegestus in human form (with colored contact lenses) and in his later transformed appearance with neck and facial prosthetics

While there is much more in the novel, who these two character really are, where they come from, and why there are here is left completely unanswered in the film. We just get the impression they are very ancient and immortal beings, somehow physically linked as brothers or twins, and that some great battle took place between the two over five hundred years in the past. This has resulted in one being imprisoned as a non corporeal spirit under the keep and the other forever charged to watch over him. Maybe that is all the explanation the film needed. Other clues in the film indicate these two beings are responsible for the creation of the vampire myth (the same idea in the book, but the villain was only masquerading as a vampire there). Glaeken has no reflection in a mirror, seduces Eva easily as if he has some type of hypnotic control over her, and is immortal. Molasar sucks the life out of his victims, leaving only drained empty husks of their bodies, and silver crosses seem to cause him physical harm.

Not much in the way of design art, props, costumes, or behind the scenes photography exists from the film today. According to Bob Keen, the special effects workshop director on The Keep, Michael Mann had all of the concept design drawings, photos, and video destroyed after filming was complete. I have a collection of several magazines with behind the scenes photos and interviews published at the time that give a glimpse into the production however.

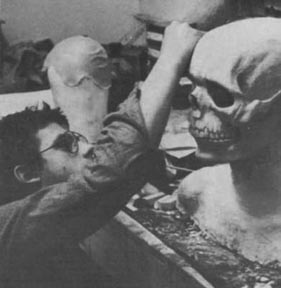

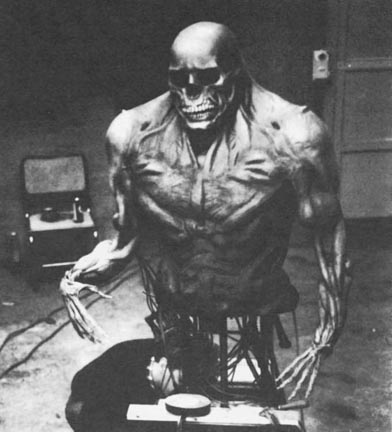

Below are photos showing the stage 1 Molasar prop, and the original mechanical stage 2 Molasar prop built by Nick Allder and Nick Maley. Michael Mann was not happy with the footage shot of this version, so it was scrapped and stage 2 Molasar was redesigned.

The stage 1 Molasar prop, and how it appeared in the film with the recycling smoke effects

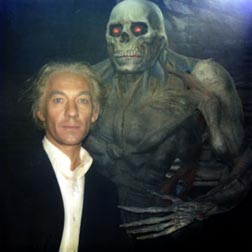

The first version of Nick Allder and Nick Maley's mechanical stage 2 Molasar prop (left, middle), and Actor Ian McKellen with the same prop on set (right).

The Keep film photos by Graham Attwood, copyright Paramount Pictures. Other photos copyright the respective copyright holders.

Website and contents ©2005, ©2007, ©2013, and ©2017 Kit Rae. All rights reserved. Linking to this website is allowed, but copying the text content is strictly prohibited without prior authorization. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any other form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, computer networking, or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the copyright holder(s).

Kit’s Secret Guitar, Gear, and Music Page

Guitar stuff, gear stuff, soundclips, videos, Gilmour/Pink Floyd stuff, photos and other goodies.

Copyright Kit Rae.

VISIT MY SWORDS, KNIVES and FANTASY ART WEBSITE www.kitrae.net